How should we communicate on climate issues in the midst of a polycrisis?

26.09.2022

The challenge of communicating on climate change in a world wracked by crises was the focus of the “K3 Congress on Climate Communication” held in Zurich earlier this month. The congress was attended by around 400 media professionals and representatives from NGOs, government agencies, public administration, political parties, and academia from German-speaking countries. The latest climate science and trends in climate communication were analyzed, discussed, and reflected upon in keynote speeches, debates, workshops, performances and films at the two-day event.

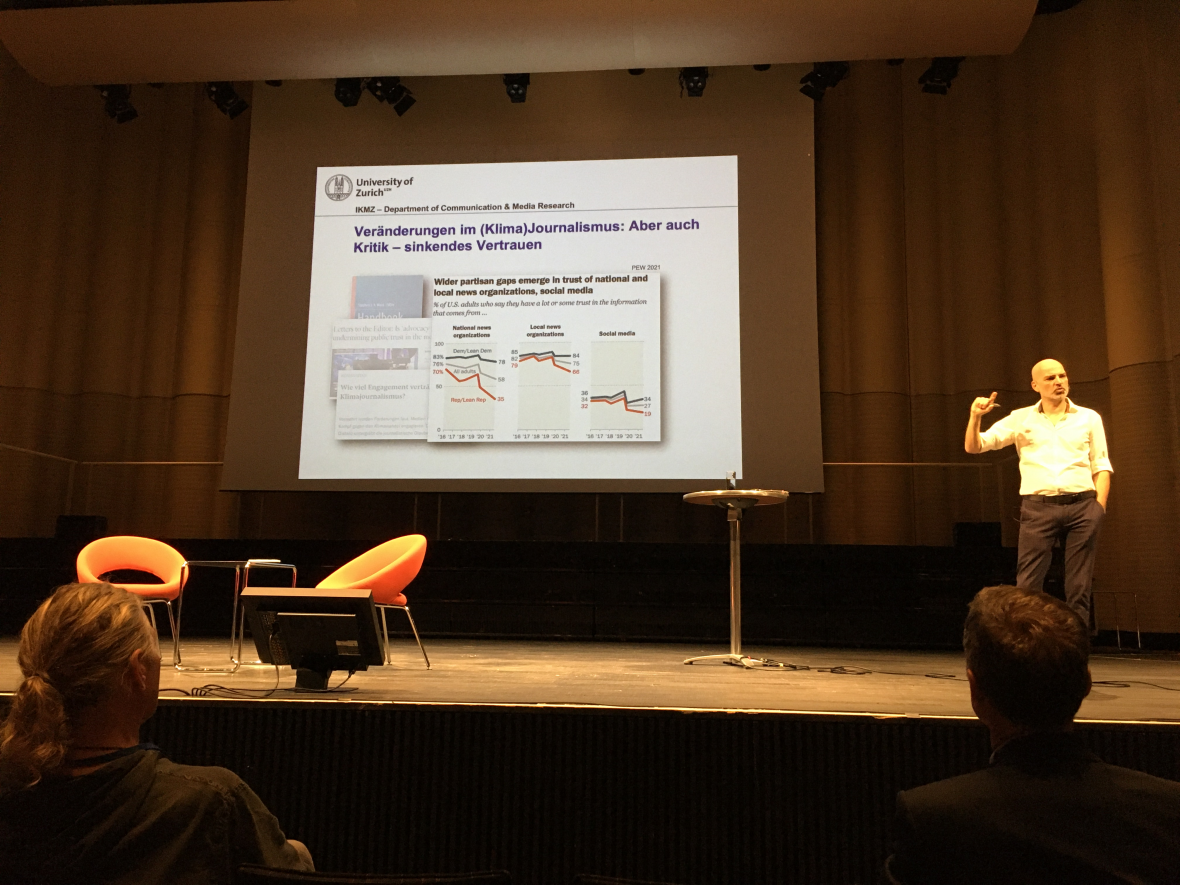

In his keynote speech on the current state of climate communication research, Prof. Mike Schäfer from the University of Zurich traced the growing visibility of climate issues in the media since 2000. The number of publications on the subject has continued to increase over the last decade, accompanied by countless studies in Western countries and the emergence of new professional associations. Parallel to this, the rise of the Fridays for Future movement has led to spirited debate on the dividing line between journalism and activism. The use of accompanying images in articles and messages on the climate crisis has also become the subject of debate, along with the semantics of climate communications. Should we be talking about a “climate crisis” or a “climate catastrophe”? Or would “climate emergency” be a better term?

Trust in the media has declined in recent years, Schäfer noted, spurred by populists, activists and the rise of alternative media. Schäfer termed this a “structural transformation of the media ecosystem.” Nevertheless, traditional journalistic media – and especially print media – are still broadly speaking the most important points of reference. Content from traditional media is also very present in social media, he said.

Prof. Michael Brüggemann of the University of Hamburg came to similar conclusions in the workshop “Journalism and Climate Change”. Long-term monitoring studies show that reporting on climate change is still a marginal topic beyond the scope of climate summits and headline-making protest actions. Just two to four percent of the articles evaluated by Brüggemann’s team contained the word “climate.”

It is only since 2018 that a relevant increase has been observed and awareness of the climate emergency has grown, he said. In Germany, this development has been driven by publicly-funded TV stations in particular. “In the wake of the COP conferences, at least one in two people talk about it for about a week,” Brüggemann finds. However, the topic of “climate” is regularly side-lined by other events such as the pandemic or the invasion of Ukraine.

Translating complex science into clear statements

A subsequent workshop highlighted the challenges involved in communicating the findings of science in clear and comprehensible language: In May 2022, at the invitation of Irène Kälin, President of the National Council, a dialogue was held between science and the Swiss Parliament on the latest IPCC climate and IPBES biodiversity reports. The scientists involved in preparing the reports explained the latest findings in climate and biodiversity research to the parliamentarians.

Although the scientists were coached in advance on the use of simple language and presentation techniques to focus on specific facts and their relevance to everyday life, the dialogue was not considered a success by those involved. “Is the IPCC report what we need today?” was one question posed to this panel, which was moderated by Gian-Kasper Plattner of the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL) and Marie-Claire Graf of the Climate Alliance of Switzerland. Those involved in the discussion, such as Julie Cantalou (Green Liberal Party of Switzerland) called the IPCC report a success story and noted that “no other scientific discipline has a comparably comprehensive overview report on the current state of research.” However, publishing a report does not automatically establish a dialogue, Cantalou said.

The language used in the “Summaries for policymakers” is highly complex, Urs Neu from the Swiss Academy of Sciences (SCNAT) pointed out. “The IPCC reports are only of use to experts working in public administration.” The complex findings presented in scientific reports need to be explained in plain language in order to facilitate dialogue.

Cantalou called for the creation of interfaces between the public and science similar to those found in many English-speaking countries, where scientific institutions often have teams of so-called “brokers”, who prepare content for policymakers. She recommended that a similar communications ecosystem be developed in German-speaking countries - and not only for climate science – in order to improve the transfer of scientific findings into politics.

On top of this, more scientists need to enter the political arena, the panel concluded. Green Party politician Aline Trede, on the other hand, argued that trust builds upon confidentiality and that public meetings are therefore not conducive to knowledge transfer.

Overcoming “learned helplessness”

In her keynote address “Sustainability begins in the mind”, Prof. Maren Urner explored the neuroscience behind effective climate communications. As the human brain continues to change throughout life, and every thought can change it, the saying “I can’t do it, I’m too old for it” is simply nonsense, Urner explained. However, our “Stone Age brains” prefer to tackle one crisis after the next, which poses a problem when we are faced with multiple crises – as is currently the case. This is further aggravated by our tendency to dwell on the negative more than the positive (so-called “negative bias”). Thankfully, the capacity to learn is hardwired into our brains, enabling us to overcome our negative bias and the associated sense of insecurity and anxiety – all of which lead to a decline in IQ and poor decision-making as well as a tendency to cling to the old and familiar (“learned helplessness”).

Urner highlighted three opportunities to promote dynamic thinking: Ask “what for” rather than “against what”. Redefine groups and contexts in order to break down entrenched camps of thought. Offer “new solution scenarios” that empower people and invite them to experience agency.

The keynotes will be available shortly on the K3 website.