Was COP26 the “Just Transition” Conference?

21.12.2021

By Alice de Moraes Amorim Vogas (Alexander von Humboldt Foundation's German Chancellor Fellow) and Isadora Cardoso Vasconcelos (IASS Fellow)

The Paris Agreement Preamble states that Parties should consider “the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities.” In 2015, the International Labor Organization approved the Guidelines for a Just Transition (JT), which were meant to help countries transition to low-carbon economies through action aligned with their NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) and SDG 8, which calls for decent work and economic growth.

COP after COP, we saw the concept of “Just Transition” gain political traction. At COP22, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Secretariat published a Technical Paper about JT. At COP24 in Katowice, over fifty countries signed the Solidarity and Just Transition Silesia Declaration, a remarkable achievement in a host-country so dependent on coal. At COP25, the Climate Action for Jobs Initiative was launched by the UN Secretary-General António Guterres to advance concrete measures to put JT and jobs at the heart of ambitious climate action. For COP26, the Secretariat prepared a new Technical Paper on the JT of the workforce in the context of the impact of the implementation of response measures (responding to the impacts of climate policies).

At COP26, we saw decisions and a handful of statements, pledges, and declarations parallel to the official negotiations centered on Just Transition. But did anything change in the substance of the JT debate in Glasgow? Below, we briefly analyze some of the political moves and texts around COP26 to understand where the Just Transition debate stands after the conference’s commitments, and what opportunities arise with the increased commitments to phase out fossil fuels for climate and social justice.

1. The Glasgow Climate Pact

The main multilateral outcome of COP26, the Glasgow Climate Pact brings two references to JT, focusing on low-emission energy systems and job creation. What is new here is the recognition of the need to support developing countries in their JT. In climate finance debates up to now, no instruments have been designed or used to explicitly finance JT projects in the Global South.

As “whole of economy” approaches advance in climate debates; “Build Back Better” efforts emerge in Covid-19 recovery plans regarding the labor markets; and climate justice movements expand globally, it is becoming clearer that socioeconomic and justice aspects ought to play a stronger role in climate policy agreements and implementation.

In Glasgow, we witnessed more than trade unions reclaiming JT. Government representatives, Indigenous Peoples, women, and environmental NGOs use of JT was evidence of how the concept is going further than the usual binary approach of a trade-off between keeping jobs or promoting environmental protection. This crosscutting development also shows us that climate finance instruments that exclusively have mitigation or adaptation approaches are no longer politically acceptable to deliver the social and economic benefits needed to advance a JT in the North and South alike. Sound, facilitative instruments are needed, which leads us to a very relevant JT political commitment made at COP26.

2. International Just Energy Transition Partnership with South Africa

Through the South Africa Just Energy Transition Partnership, the USA, UK, France, Germany, and the EU committed $8.5bn to help fund South Africa’s transition from coal to a “clean energy economy” over the next five years. This novel arrangement is an important step further in the move of JT from a general agenda to a concrete project.

This partnership shows that the JT agenda is much more robust now as it builds upon at least three different elements of the climate governance agenda that are critical for transforming climate commitments into policies and action: institutions, NDC linkage, and funding diversification.

First, the establishment of the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC) in South Africa in late 2020, which has the mandate to facilitate local consultations to inform the JT debate, lays important institutional groundwork for national ownership of the agenda.

Secondly, the partnership acknowledges JT’s role in enhancing the NDC. Some countries have already committed to adopting JT plans in their NDCs, but not on the same level as South Africa did in its updated NDC submitted in 2021. South Africa’s NDC reaffirms that “just transition is at the core of implementing climate action in South Africa” and that it will “need international cooperation and require solidary and concrete support.” By articulating that JT is a goal that deserves financial support, South Africa and this partnership inaugurated a new avenue of possibilities in the UNFCCC space.

The last key element is funding. According to the Statement, the partnership should operate through “various mechanisms including grants, concessional loans and investments and risk sharing instruments, including to mobilize the private sector.” A form of climate finance that is meant to help this unfold is the Just Transition Transaction (JTT).

Similarly, the Statement on International Public Support for the Clean Energy Transition signed by developed and developing countries and national and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), presents a big opportunity to leverage financing schemes to foster the global energy transition, although it does not necessarily assume a fair one, since the text lacks language on any justice mechanisms to implement what they pledge. However, it does agree to shift international investments from fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and gas, towards clean energies by 2022. According to Oil Change International, this shift amounts to an equivalent of 38% of the annual public finance for fossil fuels provided by G20 countries and MDBs between 2018 and 2020.

To leverage Just Transition lenses in the multilateral climate governance regime, it is critical that the agenda is not one more checklist item in the UNFCCC. It must be a functioning objective embedded in both mitigation and adaptation actions and the climate finance mechanisms. Regarding these extraofficial JT commitments, “it is also extremely important that this type of ‘polylateral’ agreement is well positioned, monitored and discussed under the umbrella of the universal UNFCCC process,” as noted by the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI).

Yet one message seems to be clear: to implement Just Transition plans, we will need all types of resources: climate finance, development finance, civil society participation, public and private resources. This brings us to one of the most central political statements on JT celebrated at COP26.

3. Supporting the conditions for a Just Transition internationally

The Statement, signed by 16 developed countries and the European Union, plays a positive role in explicitly adopting a holistic approach to JT. It goes beyond the impacts on workers in the fossil industry by acknowledging the broader socio-territorial dynamics of JT and its supply chain implications.

Firstly, by supporting a "local, inclusive, and decent work" agenda, it focuses on "disadvantaged groups in the local labor market and community, such as those living in poverty, marginalized groups, women, and workers in the informal economy to achieve a transition to formality." In other words, the target groups of JT actions have expanded beyond directly impacted workers to include the entire affected community.

Secondly, by recognizing that the transition impacts whole supply chains, it brings service providers into the JT plans, who are often overlooked. Its goal of creating "equitable employment across borders" also opens an opportunity to tackle the differences and inequalities of working conditions in transnational industries simultaneously operating in the Global North and the Global South and stresses a justice and equity scale, which has been missing in international climate commitments up to now.

4. The Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance & further Just Transition platforms to watch for

Another interesting window of opportunity to foster global JT came with the launch of the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA), led by Costa Rica and Denmark. In the current scenario, where natural gas has been largely propagated as a clean energy source to support the energy transition, this initiative openly addresses gas as an unsustainable fossil alternative and pushes governments at all levels to divest from fossil fuel production. Civil society groups, such as 350.org, supported the symbolic significance of the alliance, but stressed the need to strengthen it. Civil society is now charged with the task of monitoring its implementation, pushing for more members, and making sure governments and companies’ cease of new and already existing oil and gas extraction projects goes hand in hand with the principles of equity and justice. This means that richer countries and cities that are part of BOGA have more responsibility in driving this phase-out, while also supporting developing members to do the same. Also, for BOGA to fully succeed, it must center on the needs and rights of workers and communities directly and indirectly affected by such oil and gas industries, including non-unionized, care and/or informal workers.

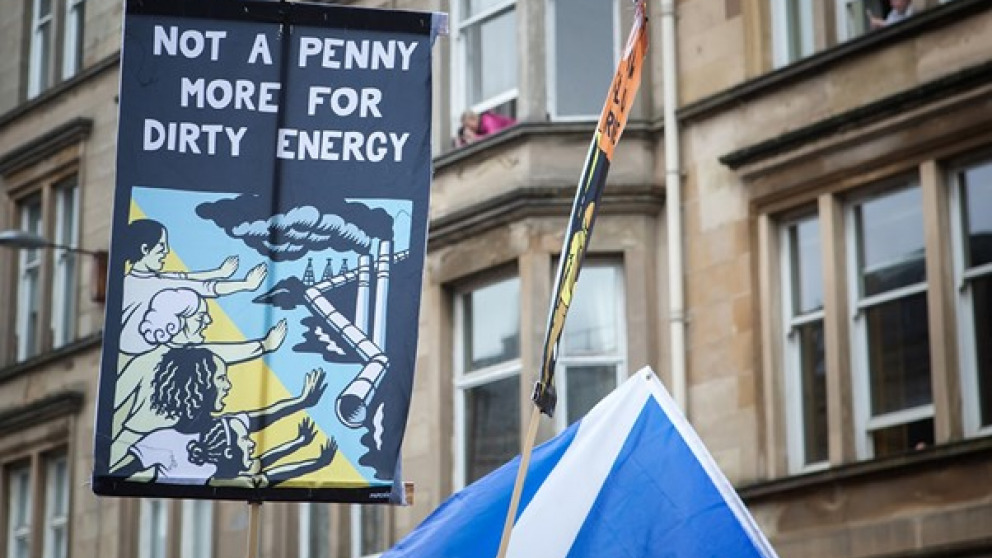

Just Transition was also very present across civil society spaces in Glasgow. At COP26, we saw remarkable civil society and research-led initiatives on JT which were not necessarily launched in Glasgow but were spotlighted this year with the prominence of the agenda. One was the global civil society campaign to establish a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty to tackle greenhouse gas emissions at their source by halting fossil supply while enabling fair economic diversification and renewable, reliable, cost-effective low-carbon solutions. We also witnessed an entire day dedicated to debating Just Transition pathways with grassroots groups, including the vigorous Scottish unions movement, in the Just Transition Hub as part of the People's Summit for Climate Justice. Finally, the Just Transition Research Collaborative has been mapping frontline JT struggles across the world while researching the development and diverse approaches of the concept itself and how it has been practiced on the ground so far. Cross-sectorial, transnational, citizen-based and contextualized evidence on JT should be increasingly supported, as the window of opportunity to drive a global just energy transition is bigger than ever given the numerous commitments made at COP26.

What’s next on the way to the Just Transition?

Despite celebrating the first call for “accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies” in a COP decision, the Glasgow Climate Pact and the various parallel declarations signed by countries and private actors on the energy transition still lack precise language and mechanisms to drive transformations in a just way. To expect that COP26 decisions and statements will automatically trickle down into JT actions on the ground is not realistic. Making signees accountable for implementing their pledges in a just way is yet another task civil society will have to keep up in the upcoming years.

All relevant actors must adopt measures to ensure justice while transitioning to low-carbon economies, including redistributive, recognitional or procedural justice instruments. In other words, the transition must be just in the manner it develops. Among others, measures must deliver more on fair financing mechanisms, such as grants, and strengthen democratic practices to enable wide, transparent, and inclusive social participation, especially of most affected people and areas (MAPAs), ensuring they enjoy benefits throughout the transition.

Ultimately, if unfair working conditions, neocolonial climate finance schemes, and unsustainable global supply chains which rely on human and environmental rights violations are not overcome, the technological shift to renewables will be neither clean nor just – as is already the case in many contexts. If in the past JT was seen as a trade-off in climate action, after Glasgow it seems that it can become more like a rail track that the international climate agenda train ought to run on in the coming decades. Among its next stops is the G7 meeting, under the leadership of Germany and its new “Traffic Light” government, which is very concerned with climate action. We hope to see progress in the implementation of commitments from the most emitting economies, in alignment with what was agreed upon at COP26.