A World of Difference? Comparing US and EU Air Quality Legislation

18.01.2021

The recent US election has inspired renewed optimism around the prospects of EU and US climate policy. The European Green Deal has positioned the EU at the forefront of climate mitigation, while President-elect Biden hopes to reclaim US leadership in the energy transition with his clean energy plan.

While these plans focus on tackling climate change, they have major implications for air quality. Biden’s clean energy plan specifically touches on the air quality benefits of a green economy, while the EU Methane Strategy, released as part of the European Green Deal, attempts to rein in methane emissions across sectors. Methane emissions are responsible not only for direct global warming impacts, but also damage human respiratory health through the formation of tropospheric ozone in the air.

Given the global influence that US and EU climate policy and legislation are likely to have in the coming years it is interesting to reflect upon the differences in how these jurisdictions approach environmental policy. In this blog post, I will explore those differences through the lens of air quality, a concern that has shaped environmental policy for more than half a century. Looking at air quality legislation, in particular, highlights some of the key differences in priorities and political feasibilities. And as I’ll show later, some of these differences are even visible when we run a statistical text analysis of the words used in EU and US legislation.

Air quality legislation: two paths

Air quality has a long history at the forefront of environmental legislation and continues to shape environmental and climate policy in the 21st century. For example, to bypass political opposition to climate policy, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under President Obama made use of existing air quality laws – under the US Clean Air Act (CAA) – to regulate greenhouse gases, on the legal grounds that they posed a danger to “health and human welfare”. While the modern EU emissions trading system focuses on greenhouse gas reduction, it was partially inspired by the US sulfur dioxide allowance trading program, originally implemented to tackle regional effects of acid rain.

Comparative analyses of US and EU air quality policy highlight several key distinctions between the jurisdictions, which are largely rooted in their respective histories. The US air quality regime evolved from the Clean Air Act of 1963; this was followed in 1970 by the establishment of the EPA and a legislative amendment that granted it wide-reaching federal enforcement powers. Later, under the neoliberal reforms of the Reagan administration, many of the agency’s powers were reduced or devolved to the states, with environmental policy tools increasingly reframed to prioritize economic measures of success. The last major “success” for US air quality policy, before widening political polarization pushed environmental topics into an intractable position, came in the 1990 update of the US Clean Air Act, which set the legal basis for the future sulfur trading system. Since then, US legislation has been characterized by scholars as focused on economic efficiency, the need to prevent market interference, and subordinating the public health risks of air quality to these priorities.

The EU’s clean air regulations followed a very different path, partly because the EU is made up of sovereign states with strong and varied national legislations. Early Environmental Action Programmes (EAPs) largely left it to member states to establish their own national regulations. That changed in the 1980s, when German government and industry forces, motivated by public outcry over the effects of acid rain on forests (Waldsterben), lobbied the EU to adopt harmonization measures on air quality to prevent undue competition. Despite pushback against EAPs by member states and the re-nationalization of certain responsibilities over the following decades, several pieces of key EU-wide air quality legislation emerged. These include the National Emissions Ceilings Directive (first adopted in 2001), which sets binding pollution emission limits for member states.

In comparison to the US approach, the EU’s legislation is widely characterized as placing greater emphasis on precautionary approaches that see environmental protection as outside of the scope of economic debates (though nonetheless shaped by economic realities) and places high importance on human health and ecological balance.

My interest in understanding these differences came partly out of my personal background, having worked on environmental issues on both sides of the Atlantic. I was especially curious to see if the US-EU differences really followed the clichés of a business-friendly US and an eco-minded EU. To help answer this question, I conducted an exploratory study to see what differences between US and EU air quality policy could be revealed from text analysis of their legislation alone.

Exploring the text

I ran a Naive Bayes Classification of comparable US and EU air quality legislation from the 1960s to 2000s to identify which words were most strongly associated with either EU or US legislation. The model incorporated various iterations of the US Clean Air Act and key EU air quality directives, and counted how frequently each word appeared in each jurisdiction’s legislation.

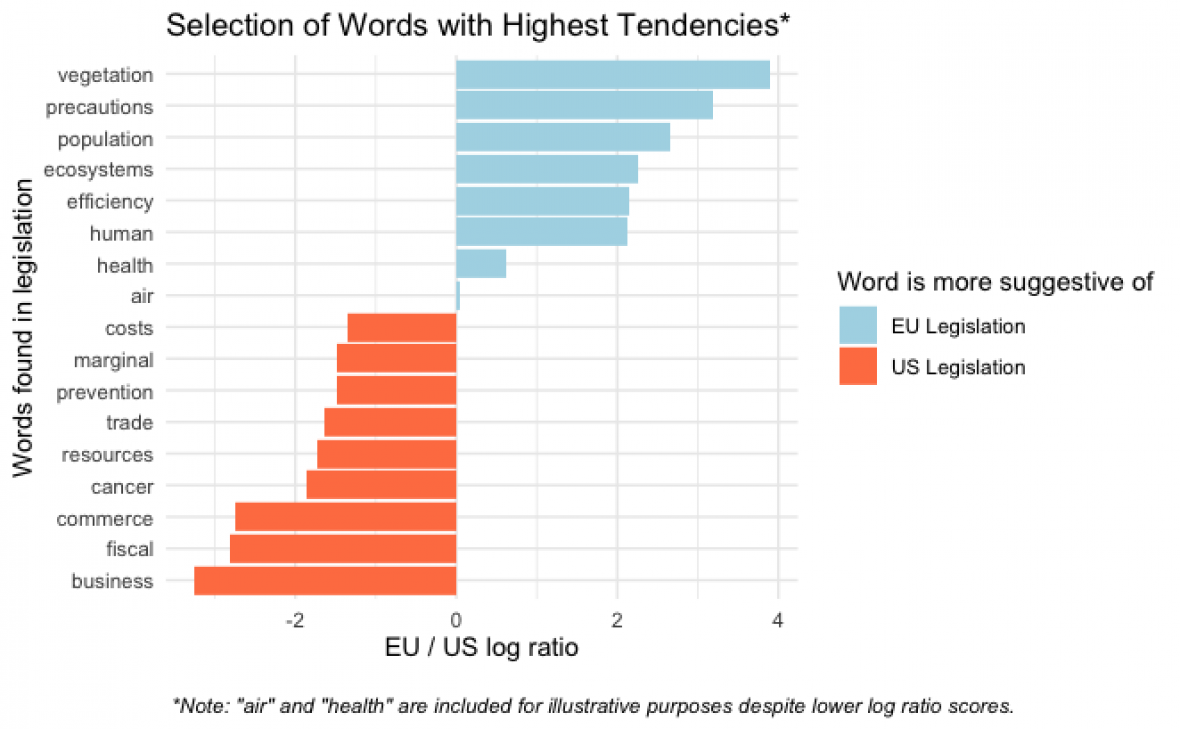

Based on the academic literature, one might expect economic words like “efficiency” and “business” to be more prevalent in US legislation, whereas words associated with environmental and human health, such as “cancer” and “ecosystems”, might be more strongly associated with the EU. I ran a list of such topic-relevant words through the Naive Bayes model to find out in which jurisdiction’s legislation each word was likelier to occur. This produced a tendency score for each word. Words that are equally prevalent between the jurisdictions, such as “air,” will have low scores, while words that show up disproportionately in one jurisdiction’s text will have a more dramatic score. The graph below shows the result for some of those words, selected based on the strength of their suggestiveness in either direction. The further a word’s bar reaches to the right, the more that word indicates EU air quality legislation; the further a bar reaches to the left, the more it indicates US legislation.

A brief glance at these scores shows they fall more-or-less as expected. Key business-friendly words like “business” and “fiscal” are strongly associated with US laws, while eco-centric language like “vegetation” and “ecosystems” suggest a more European origin. All this seems to highlight some of the above-mentioned differences that have been described in scholarly literature.

That said, the strong American association with “cancer” and the EU’s association with “efficiency” in this text analysis remind us to take any continental generalizations with a grain of salt. There are, after all, cases where US air quality legislation is actually more stringent than the EU’s, such as in its limits for ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution.

In the end, because the Naive Bayes model only looks at how often words are used, rather than their actual meaning in context, it is important not to put too much weight on a single word’s score. For example, while the strong EU tendency of the word “precaution” supports observations in the literature, US legislation is still more likely to use the word “prevention”, which has a similar meaning. Nonetheless, this exploratory analysis demonstrates how text classification models, when coupled with qualitative research, could help point researchers towards tendencies and discrepancies in comparative studies of policy and legislation.

Finally, although this analysis helps us see some of the differences in US and EU air quality legislation, it is worth noting that the two jurisdictions also have much in common. Through the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP), the US and EU have increasingly been collaborating on air quality policy, making it harder to draw a clear cut distinction between two separate paths.

The full R script and dataset for this analysis are available at github.com/adinaspertus/airlegislation

Adina Spertus-Melhus is completing her Master of Public Policy at the Hertie School in Berlin and supports the ClimAct Group at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS). Her previous work and research has focused on topics in environmental health, climate change, and circular supply chains.