The Impact of Narrative Messaging on Behavioral Change towards Sustainable Diets: Results of US Survey

10.12.2020

Food consumption and production are one of the key entry points available to human societies for effecting a transformation towards sustainability. Food production is a major contributor to a whole range of environmental problems including climate change, biodiversity loss, water overuse, and air and water pollution. Also, unhealthful diets cause chronic disease and millions of premature deaths around the world each year.

One common link between these two unsustainable trends is high levels of consumption of animal products — meat, dairy, eggs, etc., particularly in industrialized countries, but also increasingly in developing countries. Thus, efforts to shift diets en masse away from animal products towards plant-based foods can reap multiple sustainability benefits.

Lifestyles and the power of narratives

Lifestyle or demand-side changes, though considered a necessary part of sustainability transitions, can be especially difficult to promote in free, democratic societies. In the case of food consumption, people's choices are very much intertwined with identities and values, so public education campaigns or policies that aim to change diets need to develop strategies to overcome the likelihood of limited results or even outright rejection.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the importance of narratives in shaping people's existing views towards sustainability issues and the power of communication through narratives to shift those views. The term 'narrative' is often used interchangeably with 'story,' though it is broader and can be used in contexts such as 'life narratives' playing a role in individual and collective identity formation. Narrative communication, in contrast to logical, scientific-style explanation, has characteristics such as the ability to hold an audience's attention, transport them to another world, and generate understanding of characters and their emotions.

In the area of diets, a substantial amount of research has shown differences in attitudes towards meat consumption based on gender, age, political ideology, and other socio-demographic variables, suggesting the influence of different identities. This has led to the development and testing of tailored approaches to public communications for encouraging reduced meat consumption suitable for different parts of the population.

For example, narratives about health- and strength-promoting plant-based diets may inspire men more, in general, than narratives about benefits of reduced meat consumption for the welfare of animals or the environment. However, there is almost no published research dealing with attitudes and behavior specifically related to reduced dairy consumption. And the effects of gender and other factors may be different for dairy compared to meat.

Messaging approaches for encouraging reduced dairy consumption

As part of an IASS Fellowship, I designed a study to test the impacts of different messaging approaches on attitudes and intentions to reduce dairy consumption, focusing on the US, where I am from. In addition to helpful interactions with Dr. Ilan Chabay and other IASS researchers, I benefitted from a collaboration with a US non-governmental organization, Switch4Good, which had already produced a large amount of communication materials in video and other formats featuring stories of champion athletes, physicians, and others who have benefitted from cutting their dairy consumption.

We decided to focus our attention on a number of message characteristics: the rationale for dairy reduction (health benefits, environmental protection, or addressing the injustice of promoting dairy to racial minorities with high rates of lactose intolerance), the degree of 'narrativity,' the type of speaker (athlete or scientist), the gender of the speaker, and the format (video or text transcript). We were also interested in discerning relationships between message impact and the socio-demographic and political characteristics of the message receivers.

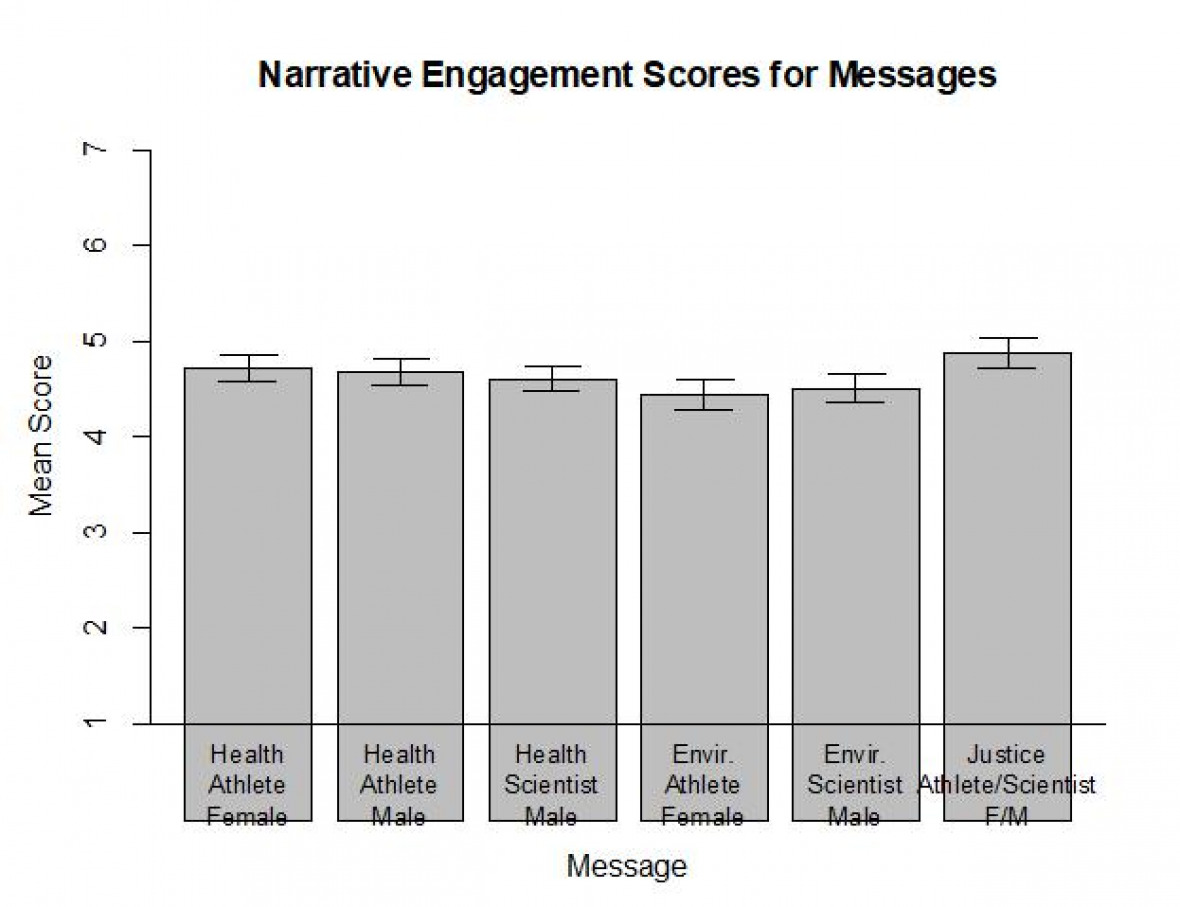

We developed a survey to assess people's attitudes and behaviors towards dairy before and after exposure to a message randomly selected from within a set of eight. Over 2600 complete responses were collected this past summer, representing a good diversity of ages, races, education levels, geographic locations, political views, and other characteristics. My analysis to date shows small but noticeable differences in how respondents rated the narrative engagement quality of the different messages (Fig. 1).

The athlete messages received slightly higher scores than the scientist messages in general, consistent with the more personal, story-like design of the athlete messages versus the more straightforward, factual style of the scientist messages. (The low-scored 'Environment Athlete Female' message is an outlier, probably for reasons particular to that message which I will not discuss here.) The racial justice message received the highest score; recent heightened awareness of societal injustice may have had an influence here.

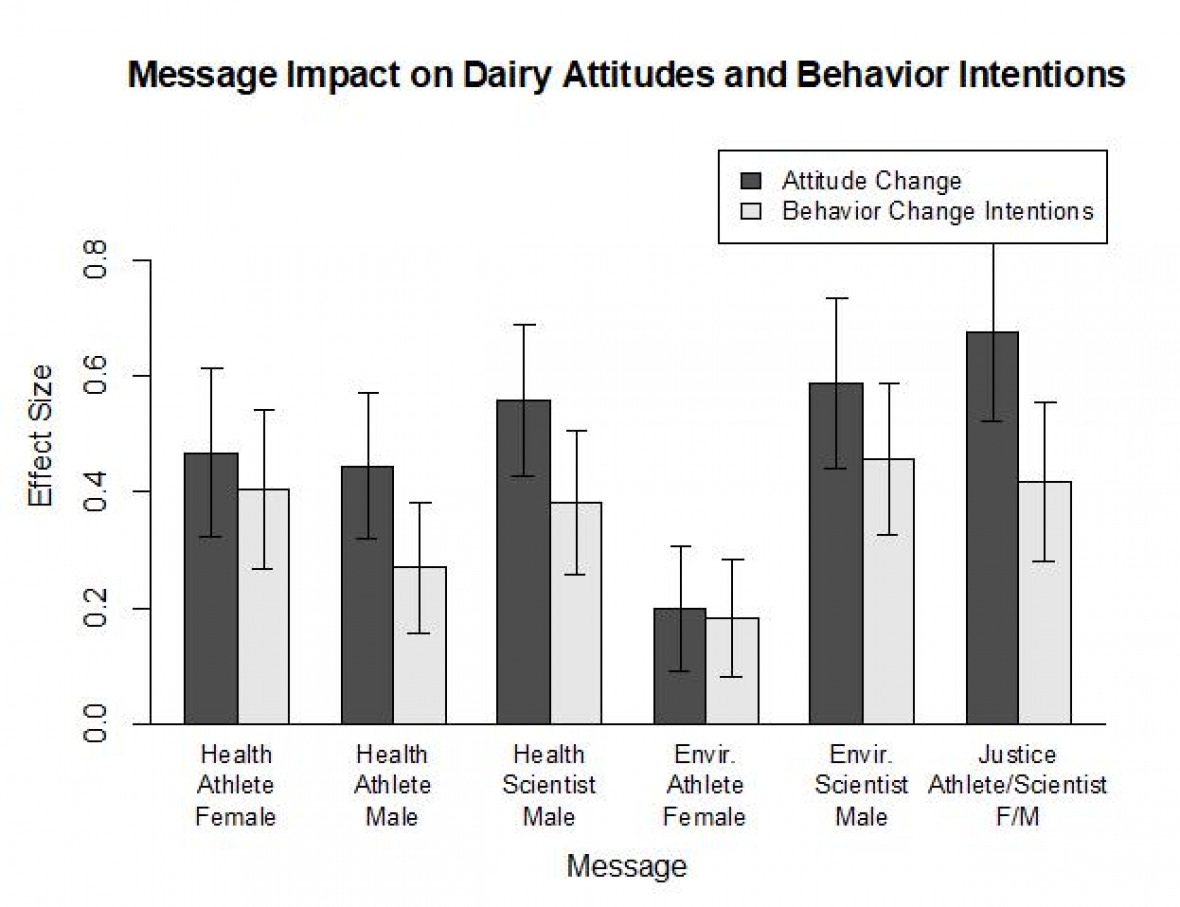

Surprisingly, the messages presented by scientists generally had larger effects on attitudes and behavioral intentions than the messages presented by athletes (Fig. 2), despite the lower narrative engagement scores of the former. Given that the respondents are well distributed across education level and other socio-demographic characteristics, the results suggest that messages that are delivered by experts and focused on facts rather than emotions can actually be broadly persuasive.

Interestingly, the justice message had a relatively large effect on not only respondents' attitudes towards dairy but also their intentions to reduce or quit dairy consumption. It could be illuminating to examine further whether that effect is found mainly in respondents of color, who ought to have higher rates of lactose intolerance and could have been made aware of the linkage between race and digestive problems by the message.

There is no consistent difference between video and text formats in the effect sizes (not shown). This contrasts with the narrative engagement scores, in which video appears to be rated somewhat higher than text.

Figure 1. Mean narrative engagement scores for messages given by dairy-consuming respondents. Scores are aggregates of a number of related characteristics such as message believability, attention holding, and emotionality. Results for the two text-format messages are not shown. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Effect sizes (difference between pre- and post-exposure values) for messages on dairy attitudes and behavioral change intentions, averaged over dairy-consuming respondents. An effect size of 1 represents the difference between, for example, 'Very important' and 'Important.' Results for the two text-format messages are not shown. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Note that the respondents who currently do not consume dairy are separated out in order to avoid distorting the results, given that the effect sizes for them are much smaller (not shown).

One factor that could have limited the impact of the athlete messages we tested is that they are presented by elite athletes and in some of the cases are addressed to aspiring athletes, so that non-athletes might not see the connection between others' athletic performance and their own health and well-being. Another factor is that the shortness of the messages (the videos being 1.5 to 4 minutes long) limits their ability to narratively engage and transport viewers.

One important caveat is that these results have not yet undergone rigorous testing for statistical significance. Another caveat is that behavioral change intention does not necessarily result in actual behavioral change. We would need to do follow-up studies to assess whether the behavior of participants has changed as they had intended.

A final note is that there is quite a bit of additional information from the survey that I have yet to fully analyze. For example, I have not delved into possible relationships between the effectiveness of different messages and socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, including gender, race, education level, political ideology, preferred forms of news media, etc. Other information includes respondents' particular concerns about dairy, their beliefs regarding specific health benefits of dairy, and other reasons for consuming dairy.

We hope that the findings of this study can help guide future efforts to promote sustainable diets and other lifestyle aspects.